Healthcare Payment and Data Security

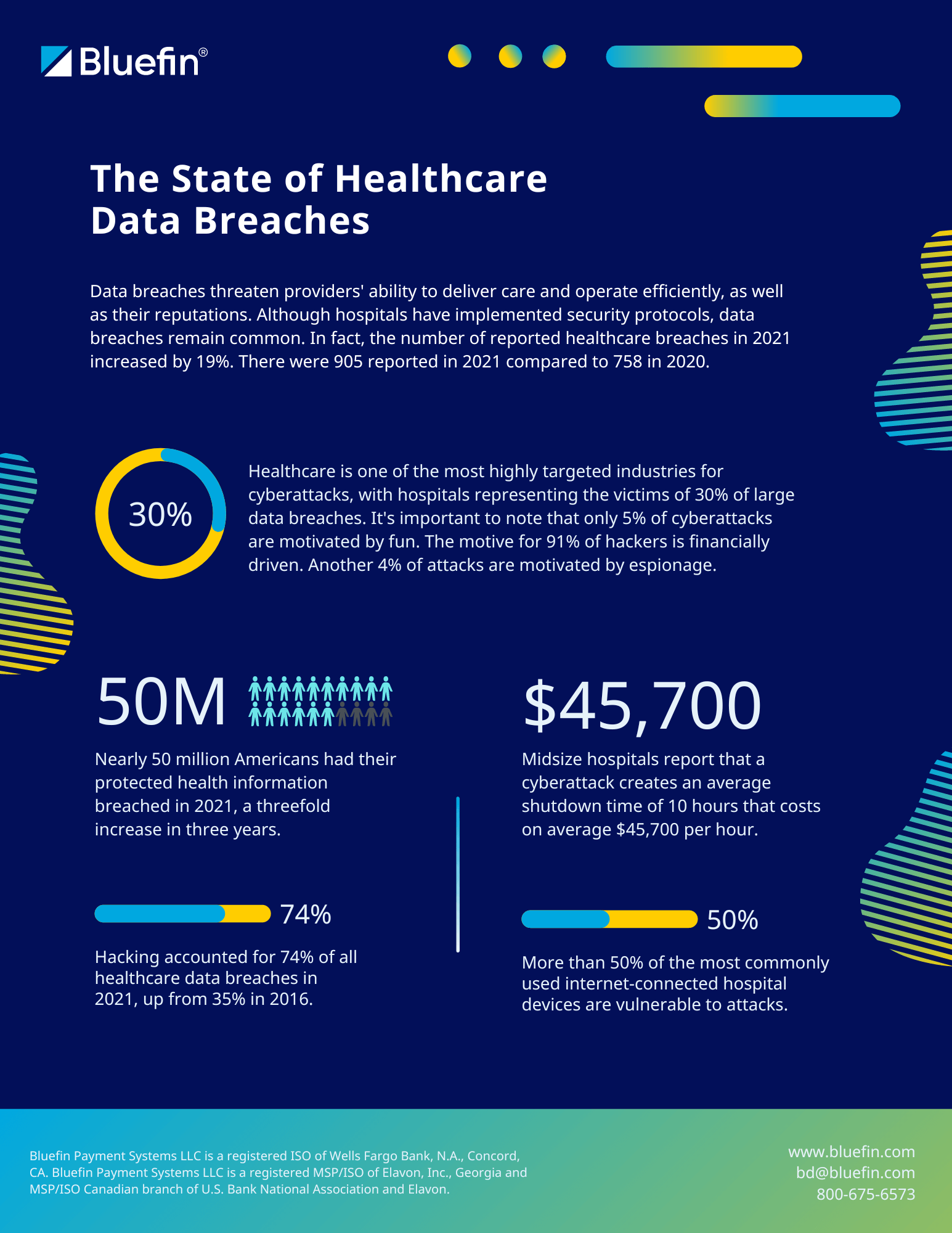

With healthcare data breaches on the rise, who’s protecting your patient data?

Bluefin’s healthcare payment and data processing solutions protect cardholder data, PHI and sensitive medical information, providing the most secure solution for healthcare payments and data.